|

|

SINKING OF

HMS BRITOMART AND HMS HUSSAR BY FRIENDLY FIRE

(Based substantially on

'Out

Sweeps' by Paul Lund and Harry Ludlam, Chapter 12, 'Savage Sunday')

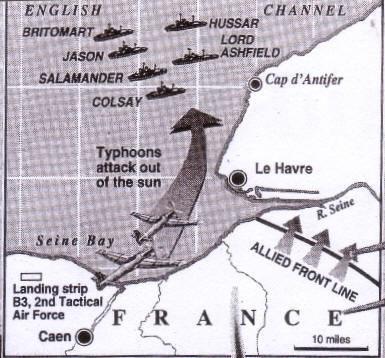

Illustration from Daily Telegraph 29th

Aug 1994

It

was late August 1944, eleven weeks after the invasion of Normandy. The

Allied armies had advanced well inland but the enemy still held Le

Havre, on the left flank of the invasion beaches, and his heavy shore

batteries continually menaced shipping. From the Le Havre area too came

E-boats, midget submarines, explosive motorboats and human torpedoes to

attack Allied shipping anchored at night around the Mulberry Harbour at

Arromanches.

Daily

off the beaches flotillas of minesweepers continued their important work

of sweeping the seas clean for the supply ships, returning to

Arromanches at night to anchor in the 'Trout Line', the defensive line

of warships formed around the merchant shipping.

One

flotilla working from Arromanches at this time, the 1st MSF was a

collection of Arctic veterans, the Halcyons HARRIER, BRITOMART, HUSSAR,

SALAMANDER, GLEANER and JASON. The 1st Flotilla's main job since

the beachhead was established at Arromanches had been to keep the swept

channel between Portsmouth and Arromanches clear of mines laid by the

enemy during the night, just where they could be of maximum menace to

Allied military transports. But on 22 August new orders came for the

flotilla, sending them to clear an enemy field of magnetic mines laid

off the German‑held coast just beyond Le Havre. The clearance of this

minefield would enable the battleship Warspite and monitors Erebus and

Roberts to move in to bombard Le Havre, helping to soften it up for

capture by the Canadian Army preparing to cross the Seine.

So,

for four days the ships of the 1st Flotilla detached from the 'Trout

Line' at sunrise each day, re‑formed as a flotilla and sailed west to

resume sweeping the minefield at the point where they had stopped work

the previous evening. The minefield was about five miles off Fecamp and

Cap d'Antifer on the enemy coast. The flotilla, using Double L and SA

sweeps for magnetic and acoustic mines, swept back and forth roughly

parallel to the coast, which was protected by the big gun batteries.

On

the fifth day ‑ 26 August, a Saturday ‑ the flotilla had twenty‑four

hours rest

'..for ships

to carry out repairs to equipment and to allow ships' companies to clean

up the decks...', staying at Arromanches. It was a depleted force now,

GLEANER, damaged by an acoustic mine, had been towed away for repairs,

while the flotilla leader, HARRIER, had also gone off with engine

trouble. So the flotilla's strength was down to BRITOMART, HUSSAR,

SALAMANDER and JASON, now the flotilla leader. However after the day's

rest they expected to return to work on the enemy minefield and it came

as a surprise when, on the Saturday evening, a signal was received

directing them to go back to their old job of sweeping the

Arromanches/Portsmouth channel the following morning.

HMS

JASON

HMS

JASON

On

board JASON Commander Trevor Crick, DSC, RN and the flotilla's

navigating officer, Lieutenant H. G. S. Brownbill, talked over this new

development. Lieutenant Brownbill:

'We knew full

well that the clearance and search of the area off Le Havre had not

been completed, and we also knew that clearance was urgently needed to

permit a heavy force to use the area to bombard the Le Havre coastal

region. Commander Crick and I discussed the position and on his orders

I went on board the minesweeping headquarters ship Ambitious to query

the orders with the staff of Captain Minesweepers. I was not received

with any particular enthusiasm as all the staff officers were at

supper. However I made my point and was promised that the orders would

be amended to allow the 1st MSF to complete its unfinished search and

clearance. Happy that all was in hand, I returned to JASON.'

The

next step was for the headquarters ship to signal the amended orders to

the 1st Flotilla, ensuring that copies of the signal were circulated to

other Service commands. All Services had to be given advance notice of

movements at sea by Allied ships, so that the smallest activity off the

French coast could be accounted for. Then, any movement by enemy vessels

could be detected and swiftly dealt with by RAF planes operating from

landing strips inland. So Naval signals to ships involved were sent

'repeat FOBAA (Flag Officer British Assault Area), repeat C‑in‑C

Portsmouth, repeat RAF,' and so on. The amended signal 'Cancelling our .

. .' etc, and redirecting the 1st Flotilla back to the minefield off Cap

d'Antifer was duly received by JASON and her small flock early on Sunday

morning (27 August) not long before the ships were due to weigh anchor.

They steamed west along the coast and resumed sweeping operations.

It

was a beautiful summer's day, sunny and warm, with scarcely a cloud in

the blue sky and the sea as calm as a duckpond. Ideal conditions for

sweeping. Round about noon an RAF reconnaissance plane flew over low.

They waved, and the pilot waved back.

1.15 p.m. The

flotilla had swept two laps in formation, but HUSSAR's magnetic

minesweeping gear had broken down so she now took up the rear. She was

due to go to Harwich for boiler cleaning the next day, so in addition to

the fine weather and the ship's inability to take an active part in the

sweep her company were all feeling particularly relaxed Men off watch

came up on deck to sunbathe, as some also did in the other sweepers, and

in the two dan laying trawlers which accompanied the flotilla.

Les

Williams on BRITOMART:

'It

was a perfect day. Most of BRITOMART's crew were sunbathing on the

upper deck. Even the duty watch were stripped off at their guns.'

In

dazzling sunshine the flotilla began its third lap, steaming along at

nine knots. JASON was guide in the centre with BRITOMART on her

starboard wing and SALAMANDER on the port wing nearest the shore, with

HUSSAR as follow up ship. The trawler COLSAY began to lay a new line of

dan buoys 600 yards on the beam inshore of SALAMANDER, while the other

trawler, LORD ASHFIELD, took up the previous line of dans.

In

BRITOMART they were all feeling especially happy because her captain,

Lieutenant‑Commander A. J. Galvin, DSC, a senior and very popular RNR

officer, had just before sailing received a personal signal from the

Admiralty conferring his 'brass hat'. The happy atmosphere was noted by

a newcomer to the flotilla, Lieutenant Commander Harold Johnson, RNR:

'I was due to leave soon for Canada to commission an Algerine

sweeper, and was sailing in BRITOMART to gain experience of the

acoustic part of Double L sweeping. This I found was in its clumsy

infancy as far as BRITOMART was concerned ‑ a truly medieval

set‑up!'

1.30 p.m. JASON

had just made the first dan of the new lap when suddenly a flock of

planes came screeching down out of the dazzling sun and attacked

BRITOMART.

Hawker Typhoon 1B in 263 Squadron markings

Hawker Typhoon 1B in 263 Squadron markings

A Hawker Typhoon 1B in 266 Squadron markings

A Hawker Typhoon 1B in 266 Squadron markings

Les

Williams on BRITOMART:

'When

the lookout shouted, “Aircraft on the port side”, everybody got up,

but we couldn't see anything because the sun was shining straight in

our eyes. Then the lookout called, “They're friendly aircraft”. I saw

the planes diving towards us. The black and white stripes which allied

aircraft had in those days were quite plain, so we thought they were

just making a practice attack. Then suddenly I saw flashes coming from

their wings. I yelled “Duck!” and flung myself down the nearest hatch,

about six feet away.'

JASON

immediately opened rapid fire with her Oerlikons, but as the planes

which had swooped on BRITOMART gained height and circled away their

markings were clearly seen and they were recognized as rocket‑firing

Typhoons.

It

couldn't be. Impossible. Yet there was no mistaking the markings.

www.grieme.org www.grieme.org

Thomas Jackson on HMS JASON:

'We set

sail at dawn for the coastal area, a glorious Sunday sunny day sea

calm. I had

the forenoon watch on the bridge. At noon Ted relieved me, I went

below for my lunch. Suddenly there were explosions and action

stations sounded. My action station was the flag deck below the

bridge. When I came on deck, I saw one ship listing badly, the crew

abandoning ship. As I approached the ladder to the bridge, I saw two

spitfires heading for the ship at sea level. The first one opened

fire on the ship. I dived behind a locker.’

1.32 p.m. JASON

sent the W/T signal, 'Am being attacked by friendly aircraft'.

1.34 p.m. The

signal was repeated. Commander Crick, looking quickly round the

formation from JASON saw that BRITOMART was on fire and listing badly to

port, HUSSAR had also been hit and was burning.

1.35 p.m. The

Typhoons swooped again. JASON fired recognition signals. The order to

slip the Double L sweep had been given and was quickly executed to give

the ship greater freedom to manoeuvre, she increased speed to full and

began to zig‑zag. But SALAMANDER was hit aft by rockets and was

immediately on fire, while COLSAY disappeared from sight under huge

waterspouts. At the same time, although all her guns were in action,

severe cannon‑fire raked JASON from the bridge to the after end of the

boat deck, killing two ratings and wounding five others, putting the

starboard after Oerlikon out of action. The hail of shells also cut a

steam pipe to the siren and the shrieking of the escaping steam made it

almost impossible to be heard on the bridge. Then it was realized that

BRITOMART had been hit again. Another quick look round when the aircraft

flew off showed that BRITOMART was still burning and under way with a

worse list to port, SALAMANDER was heavily on fire and stopped, while

HUSSAR was still steaming but fiercely on fire and enveloped in smoke.

COLSAY had miraculously reappeared from under the giant waterspouts but

was stopped and did not answer to the Aldis lamp.

HMS

COLSAY – Dan laying trawler HMS

COLSAY – Dan laying trawler

1.37p.m. JASON

signalled, 'Three ships hit and in danger of sinking'.

1.40 p.m. The

aircraft attacked again. JASON flashed another recognition signal but

was menaced by a cannon firing Typhoon diving low. A hail of fire from

the remaining Oerlikons caused it to swerve away at the last moment and

little further damage was done.

Now

all the planes flew off. It was over, eleven minutes of terrifying

assault had resulted in an appalling scene of destruction. Two reeling,

burning, sinking ships, another heavily damaged and ablaze, the sea

strewn with debris and men struggling for their lives.

This

is how death struck at each ship (CLICK on name)

1.42 p.m. As

SALAMANDER drifted helplessly, Commander Crick steamed JASON to the help

of his stricken flotilla. HUSSAR had just sunk up to her bows.

BRITOMART, a mile away, was circling slowly with a big list, badly on

fire, and survivors could be seen abandoning ship. JASON closed at full

speed signalling the trawlers to 'Save life'. But there was no answering

signal from COLSAY. Unknown to Crick, the trawler's signalling equipment

had been shot away ‑ neither trawler had escaped being sprayed with

cannon shells by the Typhoons. JASON stopped when less than half a mile

from BRITOMART fearing she might blow up, and lowered both whalers to

pick up survivors. There were many rafts about and men in the water were

hanging on to the sinking sweeper's Double L tail. JASON wirelessed for

help ‑ 'Send tugs at once'.

Thomas Jackson on HMS JASON:

'I had

volunteered for the ship's whaler which was being lowered on the port

side. Now I'm in the whaler, rowed by a team of 8 men with me as the

signalman, and my ship is sailing away. Then for the first time I

witnessed the scene, vast areas of the sea on fire, bodies floating,

cries for help. Then the leading seaman of the whaler told us to get

overboard and swim out to the Carly Floats, which had been released

from the ships. We pulled them in and tied them up to the whaler,

pulled them around the area so men could clamber on board, then myself

and the other lads on the whaler went overboard to anyone shouting for

help to bring them to the floats.'

'Eventually we could do no more as we ourselves were full of the oil,

the smell was overpowering. Eventually as we sat there it was quiet

except for the cries of those burnt.'

'Suddenly on the horizon a high speed launch was heading for us.

Cheers went up. But then I remembered a signal about the area being

open to German E Boats. As the launch got nearer we got over the side

of the whaler and hung on to the side. The boys on the Carly Floats

played dead. Then there were cheers as we spotted on its bows, the

bulls-eye insignia of the RAF. It was an RAF rescue launch. The launch

then took us on tow. Then an hour later one of our new frigates "HMS

Calypso" came on the scene. Once on board the frigate I got a shower,

a double rum and change of clothes.'

Leaving her boats to do their rescue work JASON steamed on to the

battered SALAMANDER. She now had her fire under control but with her

stern blown off she was totally unable to steer and the tide was taking

her slowly towards the enemy shore. Cmdr. Crick decided she could be

left for a short time while he investigated the silent COLSAY. As he

closed the trawler he looked back and saw BRITOMART, still burning,

capsize. By now an RAF rescue launch had arrived and begun to pick up

survivors.

COLSAY was stopped close to HUSSAR, whose bows were still above water,

but she appeared to be abandoned. There were boats, rafts and men in the

water. JASON put down her scrambling nets and got thirteen survivors on

board ... then the German shore batteries opened fire. At first the

enemy shots dropped short and JASON continued to help pick up survivors,

but then the shells began to fall uncomfortably close. COLSAY was now

within hailing distance and answered that all was well with her 'except

for a few casualties'; in fact the trawler's commander had been wounded

in the back and another officer and three members of the crew had also

been wounded, but the rest of her company were in boats and rafts trying

to pick up men from HUSSAR. Then a shell landed less than 100 yards from

JASON ‑ it was time to go. COLSAY was ordered to get out of range at

full speed and send back a boat to help the survivors, while JASON,

shouting to the men in the water that she had to leave them but that

ships' boats would be sent, put on emergency full speed and steamed

towards SALAMANDER, making smoke by all possible means to confuse the

enemy gunners as she went.

In

the water, as the fire from the shore batteries continued, HUSSAR's

wounded and helpless Commander Nash had the terrible experience of

seeing surviving members of his crew suffer the ordeal of the German

guns.

'All

my men in the water had drifted away a little, closer to the shore,

when the German shells started exploding all around. Shrapnel from the

shells, which burst on impact with the water, killed many men,

including the first lieutenant, by hitting them in the head. This was

the most dreadful part, a harrowing scene. Then the gunfire lessened.

I was eventually, after an hour or so, hauled into a Carley float by

two of my crew, a previous cork raft near me had been too full of men

to take any more. Finally a boat from a rescuing minesweeper of

another flotilla picked us up.'

Lieutenant‑Commander Harold Johnson of BRITOMART, whose ankle had

swollen enormously from a split ankle bone, was eventually picked up out

of the sea by a ship's whaler.

'We

were transferred to the RAF launch, on board which there were some

pretty terrifying cases, but all displaying amazing courage. There was

a petty officer from HUSSAR with not only his right arm and shoulder

missing, but a good part of his rib cage too. He was half lying, half

sitting, chain smoking, with this dreadful mess exposed to a glaring

sun. I dropped a wet handkerchief over it, but he just grinned and

said, "It doesn't matter ‑ I can't feel it anyway".'

The

petty officer was one of a total of thirty‑nine wounded survivors from

HUSSAR, including four officers. Three officers and fifty ratings were

lost.

Units

of the 6th MSF including HMS Gozo were in close proximity to

the scene of the incident, having been ordered to join with the 1st

MSF. A/B Trevor Davies describes what happened:

'As

we approached Le Havre we could see a minesweeping flotilla already at

work. As we got nearer we saw a number of aircraft – somebody said

they were ‘Ours’ – Typhoons and Spitfires – but as they looked as

though they were going to attack, our skipper ordered us to put a

Union Flag on the quarterdeck and an ensign on the masthead – which we

did in much haste. We saw the aircraft attack the minesweepers and

that they had scored hits. Some of the minesweepers were on fire. On

board Gozo, heading towards the ships that had been hit, we got ready

to pick up survivors. As we got up to them, we edged in very slowly –

there were lots of men in the water, some dead, others trying to

escape from the oil that surrounded them. We threw lines to men in the

water and to others in a whaler and helped to get them on board. All

were covered in oil, coughing and choking. Everyone on Gozo were doing

our best, although we ourselves were all devastated and heartbroken.

The Coxswain, CPO Payne, was a tower of strength and encouraged us,

particularly many of us young lads, only aged 18 and 19. Later that

day we transferred the wounded to a hospital ship. Next day the

captain again addressed the ship’s company and thanked everyone for

the way we had reacted the previous day. I remember he said that –

Yes, the Typhoons and Spitfires were British but these had been

captured and flown by the Germans. Somehow that statement made us feel

better and on the messdecks afterwards we all agreed that it was the

bastard Germans and just increased our hate for them.'

While

the rescue. work went on, with two other minesweepers coming to help,

JASON steamed fast to save SALAMANDER, drifting ever closer into the

sights of the enemy guns. JASON laid a two‑mile long smoke screen between

the crippled sweeper and the shore, then dropped smoke floats under her

lee to give cover while JASON took her in tow.

It was

now 3 p.m.

All this time the trawler LORD ASHFIELD, who had suffered six casualties

of her own in raids by the cannon firing Typhoons, had done excellent work

picking up BRITOMART survivors, a large number of whom were seriously

wounded.

Now a

destroyer, HMS Pytchley, arrived and lowered her boats to help in the

recovery operation. She carried a doctor, so badly wounded survivors were

transferred to her from the other rescue ships. She was then instructed to

sink BRITOMART and HUSSAR, both of whom had sunk by the stern but still

floated with their bows in the air.

Leading‑Seaman Roy Henwood

on HMS Pytchley:

'The

two vessels were bobbing around like corks. We had to fire several

rounds from our twin four‑inch turrets and even fire Oerlikon tracer

bullets in our efforts to send them to the bottom and remove the

hazard to surface craft. By the time we had finished it was after 8

p.m. and we laid marker buoys before leaving the scene.'

Meanwhile JASON had towed the crippled SALAMANDER back to Arromanches,

stopping to bury her own dead at sea on the way.

Leading‑Stoker Booth from HUSSAR was among the survivors picked up by

COLSAY, who after finishing her rescue work steamed back to Arromanches.

'All

the survivors on board the trawler were in a state of shock and

shivering in spite of it being a very hot day, and many were wounded.

I tried to pull a sock off an officer's foot of which the sole had

been shot away. There were many pitiful sights and COLSAY's crew did

all they could for them. When we arrived at Arromanches the wounded

were taken to a hospital ship and the rest of our shivering party put

ashore and taken to an Army camp.'

'Two

days later we were shipped back to Portsmouth. There we were

interrogated by a senior officer and given strict orders to keep our

mouths shut about the whole business.'

Don Rogers

from Hussar:

We were landed

on Mulberry harbour at Arromanches and taken to a Royal Marine camp in

an army truck. While passing through the village we had abuse shouted

at us by the locals. They thought we were German survivors.

HMS

SALAMANDER after the attack HMS

SALAMANDER after the attack

Seventy‑eight officers and ratings were killed and 149 wounded many

grievously, off Cap d'Antifer on that savage Sunday. Why did it happen?

What went wrong?

As in

most cases when ill‑starred events are deliberately ‘covered up', rumour

and counter‑rumour took over. Among those closely involved, survivors

and rescuers, the immediate anger was directed at the RAF but afterwards

the unsettling feeling grew that the blame did not lie in that quarter

but with the Navy itself. There was no official report, nor did any word

of the disaster get into the newspapers; some officers involved were

told simply that the tragic blunder was due to 'an error in

communications'.

John

Price of BRITOMART in Portsmouth some days later was told:

'...

that a group of German ships had left Le Havre the previous night,

i.e. Saturday night, and that they had been attacked. Moving up the

coast as we were and not seeing us turn at the river mouth it was

assumed that we had just left Le Havre, therefore we must be German

and the attack was ordered'.

In

fact a Court of Enquiry was held at Arromanches two days after the

tragedy. It was attended by Commander Crick and Lieutenant Commander

King of SALAMANDER, the flotilla's only unwounded C.O.'s. Also present

was Wing Commander Johnny Baldwin , DSO, DFC, AFC, who had led the

sixteen Typhoons (eight each from 263 and 266 (Rhodesia) Squadrons which

took off from an airfield in France) into the attack accompanied by a

Polish squadron of twelve Spitfires. Baldwin was an extremely

experienced Typhoon pilot, who (it is claimed) had been responsible for

the attack on the staff car carrying Field Marshall Irwin Rommel in

which Rommel had been badly injured.

|

Source: AIR 27/1557: Operations Records Book 266 & 263 Squadrons (Extracts)

Operations Record Book 266 Squadron

RAF

27th August

1944 Up 13.05 Down 14.00

W/Cmdr Baldwin

F/S Luhnenschloss

F/O D C Borland

P/O D L Hughes

S/Ldr J D Wright

F/S D Morgan

F/L D McGibbon

F/S E Donne

Five ships

attacked off Etretat, six ships located sailing south west, 4

probable destroyers, 2 m/v’s. Owing to doubt as to identity

controller was asked four times whether to attack and told that

ships fired colours. Controller said that no friendly ship in area

and ordered attack. 263 Sqdn claim R/P salvos on 2 ships, 266 on

three ships. Also straffed. Ships were our own.

Extract from daily

summary for the month:

27/8/44 The

Squadron had a very successful shipping strike, destroying two

destroyers and one minesweeper, damaging one other, unfortunately

Royal Navy shipping ordered by the mistake of the Admiralty to be

attacked and destroyed. Admiralty took full responsibility.

Operations Record Book 263 Squadron

RAF

27th August 1944

Typhoon

1B Up 13.09 Down 14.05

S/L R D Rutter

F/L L Unwin

D F Evan

F/O W G Kemp

A Barr

A R S Proctor

F/S LeGear

P/O J Thould

The target

of this operation was 5 ships off Etretat. 6 ships were located at

the given pinpoint sailing S.W. 4 were probably destroyers and 2

motor vessels. Owing to doubt as to identity, controller was asked 4

times whether to attack and was told that the ships fired coloured

lights, Controller said no friendly ships in area and ordered

attack. The squadron claims salvo on one destroyer and on a second

ship. There was some light flak.

|

It

was established that the air strike that day had been carried out at the

express request of the Navy ‑ even though about an hour and a half

earlier a reconnaissance plane which had flown over the flotilla had

reported the ships to be friendly. Further, while in the air leading the

Typhoons, Wing Commander Baldwin had repeatedly questioned his orders to

attack what he believed to be friendly ships.

Lieutenant‑Commander King:

'He

was very cut up. He was told quite firmly to attack after twice

reporting that we were friendly, and had then called up a second

Typhoon squadron to finish us off. Luckily for us, this squadron was

away shooting up a train for the Army.'

The

truth of the hushed‑up affair was that the strike was ordered by the

Naval headquarters staff ashore because they had no knowledge of the

change of plan of the 1st Minesweeping Flotilla. The Flag Officer

British Assault Area (Rear‑Admiral J. W. Rivett‑Carnac) had not been

informed that the flotilla were returning to finish their work on the

minefield off Cap d'Antifer. Therefore it was thought they were enemy

ships trying to enter or leave Le Havre.

Why

had the admiral and his staff not been informed?

Three

senior Naval officers were court‑martialled.

(Source: ADM 156/212

Attacks on HM Minesweepers by friendly aircraft: Court Martial. Case

Number 00373)

1. Lt

Cdr R D Franks DSO OBE RN FOBAA's Staff Officer, Operations. CASE NOT

PROVED

On

Sunday 27th August 1944, Franks was the Flag Officer British Assault

Area. When the ships were first sighted sweeping close in to the shore

by allied reconnaissance aircraft he was asked to confirm if there

were any allied ships in the area. He knew that minesweepers had been

clearing a channel in that area on previous days but when he consulted

the 'Daily State' produced the day before it showed that there were no

allied ships within 20 miles. He attempted to contact the 1st

Minesweeping Flotilla to confirm that this was the case but the

telephone was out of order.

2. Act Capt The Lord

Tyneham DSC RN Ret'd CASE NOT PROVED

Lord Tyneham the Captain

Minesweepers in executive command of all FOBAA's minesweepers had

overall responsibility for the issue of all orders/signals. However

with some 200 a day crossing his desk it was considered that he could

not be held responsible for this omission. Also he was away on duty at

the time, leaving his deputy (Venables) in charge on board Ambitious.

3.

Act Cdr D N Venables DSC RN (Ret'd) Commander Minesweepers

CASE PROVED: SEVERE REPRIMAND

Charged that he:

Negligently performed the duty imposed on him when

acting as Commander Minesweepers in the British Assault Area in that

he did not approve the issue of a signal, dated time group 261926/B,

August, amending the minesweeping programme for Sunday 27th August

1944 without ensuring the Flag Officer British Assault Area was

included in the address of the said signal, thereby contributing to

the cause of an air attack by friendly aircraft upon ships of His

Majesty's 1st Minesweeping Flotilla.

Venables was responsible for organising the day to day operations of

the minesweepers in this area. On Saturday 26th August 1944 orders

were prepared for the minesweepers to move from the area they had

previously been sweeping and go to a different area on the Sunday. At

about 1900 on Saturday, over dinner, Venables sitting at the head of

the table asked Lt E T Lawrence Shaw to prepare an order for the ships

to finish clearing the channel off Cap d'Antifer as it only needed one

more day's work to finish their task. This final stage of the sweeping

would take the ships close to shore.

Shaw, on his second day in post, prepared a draft order telling the

ships to complete their previous work and to stop if they came under

fire from German shore batteries. He showed the draft to Venables and

it was then typed up. Venables checked the order, commenting 'That

seems clear enough' and it was sent. What no one had noticed was that

at some stage the order had omitted to include the Flag Officer

British Assault Area as an addressee.

On

such a simple error ‑ or inexcusable negligence ‑ was the tragic fate of

the 1st Minesweeping Flotilla sealed.

There

was another sad factor, as SALAMANDER's commander reveals.

'FOBAA had a

radar station at his headquarters which was designed to cover the whole

of Seine Bay. On the morning of the attack it was out of order and not

repaired until about 1 p.m., when it picked up our flotilla. Had it been

working in the morning the operators would have seen our ships forming

up and leaving the defence line for the minefield. There was a

minesweeping liaison officer at headquarters but as he explained

bitterly to me, "No one thought of asking me." '

With

haunting understatement, the final paragraph of Commander Trevor Crick's

detailed

secret report

to the

Admiralty on the events of 27 August 1944, written on board JASON at the

end of that day, read: 'It is felt that the fury and ferocity of

concerted attacks by a number of Typhoon aircraft armed with rockets and

cannons is an ordeal that has to be endured to be truly appreciated.'

Crick received an OBE for his “coolness, courage and devotion to duty”

but as he said in a newspaper interview in 1962, “It certainly was a

queer way to get a gong”.

The

last floating evidence of that ordeal, the severely damaged SALAMANDER,

was towed across the Channel by a tug to Portsmouth, but it was a

journey with a miserable ending; she could not be found a berth, the

port was too busy with supplies for Normandy. So the tug, ironically

named Destiny, pulled SALAMANDER on up the east coast to West

Hartlepool. There she was officially 'placed in Reserve'. But she was

damaged far beyond economical repair. One day in the spring of 1947

SALAMANDER was taken in tow again, on a short and final journey to the

scrapyard.

So

embarrassed was the Navy's hierarchy by the attack that the Honours and

Awards committee at Admiralty House recommended that the bravery of Cdr

Crick and his officers in rescuing so many men should not be recognised.

But that finding outraged the Second Sea Lord, Vice Admiral Sir Algernon

Willis, who said: This was the severest attack any ships in Operation

Neptune [the naval element of the Normandy invasion] had to sustain, and

so far as the ships were concerned, the aircraft were 'enemy' because

they behaved as such." Cdr Crick was granted the military OBE and four

other Officers were made MBEs for their part in the rescue effort.

|

HMS Harrier

3rd September 1944

RECOMMENDATIONS FOR IMMEDIATE

DECORATIONS AND AWARDS

Sir,

The attached recommendations for immediate

decorations and awards to Officers and men of ships of the

First Minesweeping Flotilla and attached trawlers have been

received from the Commanding Officer, HMS JASON, who was

Senior Officer present on Sunday 27th August 1944

when the Flotilla was subjected to powerful air attack. They

are submitted for your favourable consideration.

On hearing what had happened I myself crossed

to Normandy, later embarking on HMS JASON for passage to

Portsmouth and taking the opportunity to visit ships on

their arrival. I was most impressed by the high morale shown

by all Officers and men after what must have been a most

trying ordeal. This I attribute principally to the undaunted

courage, coolness and devotion to duty shown by Acting

Commander T C P Crick DSC RN, the Commanding Officer of HMS

JASON. Commander Crick handled a most difficult situation

with the greatest calmness, not only at the time of the

actual attack but also later in the administrative work in

connection with the listing of survivors and wounded. A form

of recommendation for Commander Crick is attached herewith.

I would like to draw your attention in

particular to the conduct of Temporary Acting Lieutenant

Commander H C King, RNVR, commanding officer of HMS

Salamander, Lieutenant JHL Sulman DSC RNVR HMS COLSAY, and

Lieutenant J B Morpeth RNR HMS LORD ASHFIELD. The Commanding

Officer of HMS JASON refers particularly in his report to

the calmness and order in HMS SALAMANDER after her stern had

been blown off and states that she was taken in tow in ten

minutes. Other witnesses tell me that it was nearer five

minutes. The good work of Lieutenants Sulman and Morpeth in

picking up survivors after themselves being attacked and

while under fire from enemy shore batteries undoubtedly

saved many lives. Lieutenant Sulman was himself wounded in

the back but refused all medical attention until he had

brought his ship back to harbour.

The loss of two good ships and serious damage

to a third with the loss of so many gallant comrades under

such tragic circumstances are heavy personal blows but I am

consoled in the knowledge that the conduct of all concerned

was in the highest traditions of the Royal Navy and I am

very proud of them.

Signed M N H

Nicholls, Commander Royal Navy

|

When describing

the events 50 years later, John Price of HMS BRITOMART wrote:

'The

initial feeling when the attack starts is one of anger. I am

sure that there were a good many ratings that day who were

raging in their hearts at "those stupid bastards" who couldn't

distinguish a White Ensign from a German flag. Going out on

deck would, I fear, have been tempting fate. This rage does

stay with you for a long time.'

'On reflection, much later, you realise that with no wind and

an ensign hanging down like a dirty duster, they couldn't

recognise it anyway. Strangely enough in later life, whenever

I've thought about what happened that day, it's not bitterness

I've experienced but sadness that so much young life was

ruined, and in many cases ended because of an accident that

probably could have been avoided if someone had taken the

trouble to check movements.'

'I was lucky, it taught me to value life. Those who were

disabled or crippled for life after it, probably feel bitter

about it, and who can blame them?’

|

|

Ensign’s tragic

tale

WANDERING along the

beach of the French port of Villiers-Sur-Mer, a small boy picked

up a large tattered White Ensign that had been washed ashore and

kept it as a souvenir.

Over forty years later

he handed it in to the British Ministry of Defence, and steps

were taken to discover its origins, through the letters column

of Navy News.

Now it appears that the

full tragic story has been finally pieced together and the

ensign is from HMS Salamander, a minesweeper operating off the

French coast in 1944 and mistakenly attacked and sunk by British

aircraft.

Operating with two

sister ships, Britomart and Hussar, Salamander had hoisted two

extra ensigns in a vain bid to identify the group’s nationality,

but the attack claimed 86 lives and a further 124 were wounded,

leaving Salamander with her stern blown off, and the other two

ships sunk.

The six foot by three

foot ensign has now found a final resting place in the Hampshire

village of Wickham, a village twinned with Villiers-Sur-Mer.

Presented to the local branch of the Royal British Legion it now

occupies a special place in the Community Centre’s special

twinning display.

[Navy News 1984] |

|

Written

Answers to Parliamentary Questions

Tuesday 21

February 1995

Friendly

Fire Incident (Normandy)

Mr. Mackinlay:

To ask the Secretary of State for Defence if he will ensure that a

memorial service is held for the men killed on HMS HUSSAR, HMS

BRITOMART, HMS SALAMANDER and HMS COLSAY in the friendly fire

incident off Normandy on 27 August 1944; and if he will make a

statement.

Mr. Soames:

It is for veterans' associations to organise the commemoration of

individual actions if they so wish. Official events commemorating

the 50th anniversary of the D-day campaign as a whole were held

last year. This year will see the commemoration of victory in

1945.

Mr. Mackinlay:

To ask the Secretary of State for Defence if his Department will

give all reasonable assistance to those wishing to organise a

reunion for those sailors who survived the friendly fire incident

of Normandy on 27 August 1944 involving HMS HUSSAR, HMS BRITOMART,

HMS SALAMANDER, and HMS COLSAY.

Mr. Soames:

The editor of "Navy News", the official newspaper of the Royal

Navy, will be pleased to publish a request for survivors of this

incident to contact the organisers of any reunion.

Mr. Mackinlay:

To ask the Secretary of State for Defence if he will lift the

embargo on the names of those who died in the friendly fire

incident off Normandy on 27 August 1944, involving HMS HUSSAR, HMS

BRITOMART, HMS SALAMANDER and HMS COLSAY, and publish the names of

those who survived prior to their dispersal to other units of the

Royal Navy.

Mr. Soames:

There has never been an embargo on the list of casualties from

this incident. Indeed, details of those from the BRITOMART and the

HUSSAR, the two vessels sunk, were published in The Times in

October and November 1944. Any casualty details from the other

vessels involved may well have been included in more general

casualty lists frequently published in the press at the time, but

these could now be checked only at disproportionate cost. The

names of those who survived would be scattered among any number of

contemporary records, and these also could now be checked only at

disproportionate cost.

|

|