Secret papers detail RAF raid on

Royal Navy

A ‘friendly fire’ mistake that

left 117 sailors dead and 153 wounded has been cloaked in

official secrecy for 50 years until now…

THE

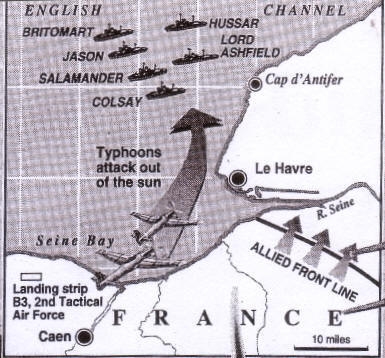

ATTACK was meticulously executed. It came out of the sun with no

warning and hardly a rocket fired by the power‑diving aircraft

was wasted as Typhoon fighter‑bombers of the RAF's 263 and 266

Squadrons ripped into the flotilla of minesweepers at 1330 on

Sunday Aug 27 1944.

THE

ATTACK was meticulously executed. It came out of the sun with no

warning and hardly a rocket fired by the power‑diving aircraft

was wasted as Typhoon fighter‑bombers of the RAF's 263 and 266

Squadrons ripped into the flotilla of minesweepers at 1330 on

Sunday Aug 27 1944.

Less than 15‑minutes later, two

of the 230 ft ships were sliding to the bottom of the English

Channel. A third was drifting helplessly its stern torn off.

But it was the wrong target. The

16 Typhoons had, in fact, attacked the Navy's First

Minesweeping Flotilla, killing 117 sailors and wounding 153. It

was the worst wartime attack experienced Royal Navy at the

hands of its own forces.

Yet, for 50 years, the mistake

was cloaked by official secrecy and nobody knew who was

responsible for it. Now, The Daily Telegraph has had the first

access to secret documents on the incident, just released at the

Public Record Office in Kew.

The First Minesweeping Flotilla (FMF),

led by Cdr TGP "Tommy" Crick , DSC and bar, in Jason, had been

operating in the same area, just off the Cap d'Antifer, for 12

days up to Aug 25 but was then moved to another part of the

coast. In the morning of Aug 26, Capt Lord Teynham, the Captain

(Minesweeping) attached to the British Expeditionary Force in

Normandy with responsibility for

the removal of mines along the northern French coast, decided to

move the flotilla to another part of the Channel.

The overall minesweeping plan was

circulated to all the necessary authorities by signal. But later

that evening, Capt Lord Teynham's deputy, (Acting) Commander

Dennis Venables, decided to change the orders and to move the

flotilla back to its former grounds off Cap d'Antifer. The

change of orders was also sent by signal but, owing to an error,

it was not circulated to the area naval headquarters, known as

Flag Officer, British Assault Area (FOBAA).

So the flotilla found itself

cruising as usual, some 12 miles off the coast of

German‑occupied France, sweeping for mines in line abreast

formation. Allied ground radar also found it at about 1200 hours

on Aug 27th. The first sightings on radar identified the

flotilla as being three to six miles off the French coast. In

that position, it was almost certainly a German formation, the

radar operators thought. Radar contacted FOBAA where staff

officers shared the assessment and alerted their commander, Rear

Admiral James Rivett‑Carnac.

Told that there was no Navy

formation in the area, according to the signals held by FOBAA,

the admiral ordered a reconnaissance of the formation and

approved an air attack if necessary. At 1220, a, Polish officer,

Sqn Ldr Wojak Retinger, flew his Spitfire over the flotilla. He

reported its position ‑ wrongly ‑ as being six miles west of the

port of Etretat but said that it

appeared to be a minesweeping convoy and was probably friendly.

But FOBAA still had no record of

a Navy formation in the area. Attempts to contact Captain

(Minesweeping) in his command ship Ambitious off Arromanches,

failed because telephone lines were down.

FOBAA requested a Typhoon strike

and 263 and 266 Sqns were ordered the air, taking off at 1305

and 1306 respectively. They were led by Wg Cdr Johnny Baldwin of

266 Sqn, a much decorated pilot who claimed to be the man who

had shot up Rommel in his staff car. Baldwin approached the

flotilla and was immediately suspicious. Sqn Leader Robert

Rutter the CO of 263 Sqn who is now 75, says: “the orders to

Baldwin were quite positive but he still queried them. Even so,

we were told to attack. I remember that Baldwin thought the ships were in the wrong formation to be German. I think he

queried it on more than one occasion.”

According to recently opened RAF

records the Typhoons sought confirmation of the attack four

times, including once between the first and second attacks after

the ships fired recognition flares. “Ship recognition was

notoriously difficult. The alternative to attacking was to risk

court martial ourselves. Suppose those ships had been German and

had sailed on and attacked allied shipping? says Sqn Ldr

Rutter.

And so the attack went on. In his

report to the Admiralty, Cdr Crick, a top‑class rugby player who

had served in Jellicoe's Navy in the 1914‑18 war, said: "The

attack came almost immediately and literally out of the blue at

13.30."

“The first that Jason knew about

it was the screaming noise of power‑dived planes overhead and

Britomart was hit. The attack came out of the sun, achieved

complete surprise and was naturally presumed to be hostile. As

the aircraft which had attacked Britomart gained height and

circled away, their markings were clearly seen and they were

recognised as Typhoons.” Jason sent the signal "Am being

attacked by enemy aircraft" within two minutes of the first

rocket‑strike. By the time it did so, Britomart, its bridge

wiped out, was listing heavily and Hussar was burning.

Another minesweeper, Salamander,

fired two coloured recognition flares but the RAF planes were

ordered to ignore them and returned for a second salvo at 1335.

This time Salamander and Colsay were hit. Jason was strafed and

Britomart was struck again.

The third attack came at 1340.

Jason fired recognition flares and the other vessels still able

to defend themselves used their anti‑aircraft weapons. A Union

flag and the largest White Ensign the horrified crew could find

were draped on the fo'c'sle but to no avail.

This time the Typhoons hit Hussar

again and she exploded. Salamander's stern was blown off and she

began to drift towards the Normandy coast and the Germans'

9.2‑inch coastal guns. As Jason began her rescue operation, the

battery opened up and she had to rely on her small boats to

attach a line to her stricken sister and tow her from danger.

When the survivors were counted,

117 officers and ratings had been killed and 153 wounded.

Hussar, the 10th Royal Navy ship to bear the name, was sunk 10

years to the day after she was commissioned. The minesweepers

were not flimsy vessels. Both Hussar and Britomart were 230 feet

long and 875 tons in weight. The RAF planes that sank them

recorded them in their logs as "destroyers".

Sqn Ldr Rutter says: "It was a

terrible business at the time. Afterwards, obviously, everybody

deeply regretted it but by then it was too late."